| Previous Chapter | Return to all notes | Next chapter |

Mathematical Functions and Expressions

In the previous chapter, we plotted the function $x^2$ as an example with

syms x

fplot(x^2,[-2 2])

However, from the point of view of a CAS, $x^2$ is simply an expression. Let’s say that we wish to evaluate this at $x=3$, we can use the subs commands as

subs(x^2,x,3)

which returns 9. This will be quite handy if we have a more complex expression (or a other objects)

syms x0 y0 r y

circle = (x-x0)^2 + (y-y0)^2 == r^2

and then we want to substitute $x=1,y=-2$, $r=3$ and we can with:

subs(circle,[x0,y0,r],[1,-2,3])

and then the result is the equation: \((x-1)^2 + (y+2)^2 = 9\)

Mathematical Functions

Above, we substituted the value $x=3$ into the expression $x^2$. Instead, we could make a mathematical function with

f(x)=x^2

and then f(3) will return 9.

This also allows us to do composition. For example, if we

syms h

then the difference quotient

(f(x+h)-f(x))/h

returns: \(\frac{(h+x)^2 -x^2 }{h}\) or if we simplify this with:

simplify((f(x+h)-f(x))/h)

returns $2x+h$ and we will see this with derivatives in Chapter 5.

Additionally, we can do formal composition. For example if

f(x) = x^3+x

g(x) = 1/(x+2)

Then f(g(x)) returns

\(\frac{1}{x+2}+\frac{1}{\left(x+2\right)^3 }\)

and g(f(x)) returns

\(\frac{1}{x^3 +x+2}\)

Exercise: composition of functions

Let $g(x) = \sqrt{x^2+1}$ and $h(x) = e^x$, find

- $g(h(x))$

- $h(g(x))$

- $h(h(x))$

- $g(g(x))$

Expressions versus Functions

Now that we see both expressions and functions, what’s the difference? When should I use one versus the other?

Recall again:

- An expression is just a combination of symbolic variables and functions.

- A function is an expression that has a name and an input variable or variables.

You can do much the same with either a function or an expression, although often the syntax will be different.

A short rule-of-thumb would be that if you are evaluating something for different values, a function is preferable.

Otherwise, either is often fine and I often don’t know when I start solving a problem the best thing to use.

Solving Equations

You probably recall from throughout your mathematical career that solving an equation can be difficult.1 Matlab can often solve equations effortlessly. For example if we type

syms x

solve(x^2-3*x-4==0)

where we need to use the double equals == for an equation. Remember that a single equal sign = is the assignment operator (set the left hand side to the variable on the right).

If you enter this, Matlab returns:

\(\left( \begin{array}{c}-1 \\4 \end{array}\right)\) meaning that both 4 and -1 are solutions to the equation.

Quadratics are fairly straightforward to get solutions for both us (mathematicians) and computers. There is factoring or the quadratic formula.

Exercise: Solving Quadratic Equations

Solve the following quadratic equations.

- $x^2-x-30=0$

- $x^2+4x+4=0$

- $x^2+2x=120$.

- $x^2+4=0$.

Note that in #3 that you can put the equation in as is (remembering the == though), you don’t need to put all terms on the same side.

Solving cubics

Matlab can handle some cubics as well. Consider

solve(x^3+6*x^2+5*x-12)

then Matlab returns: \(\left(\begin{array}{c} -4 \\-3\\1\end{array}\right)\)

Showing that $1,-3,-4$ are all solutions.

Some cubics though don’t readily have nice solutions. Consider:

solve(x^3+3*x^2-11*x-10)

which returns \(\left(\begin{array}{c} root(z^3+4z^2-3z+11,z,1) \\ root(z^3+4z^2-3z+11,z,2) \\ root(z^3+4z^2-3z+11,z,3) \\ \end{array}\right)\)

which is Matlab’s way of saying that the roots of the cubic are the roots of the cubic. (Super helpful, Matlab!) Below, we will learn how to find both the exact answer and approximations to this.

Solving Trigonometric Equations

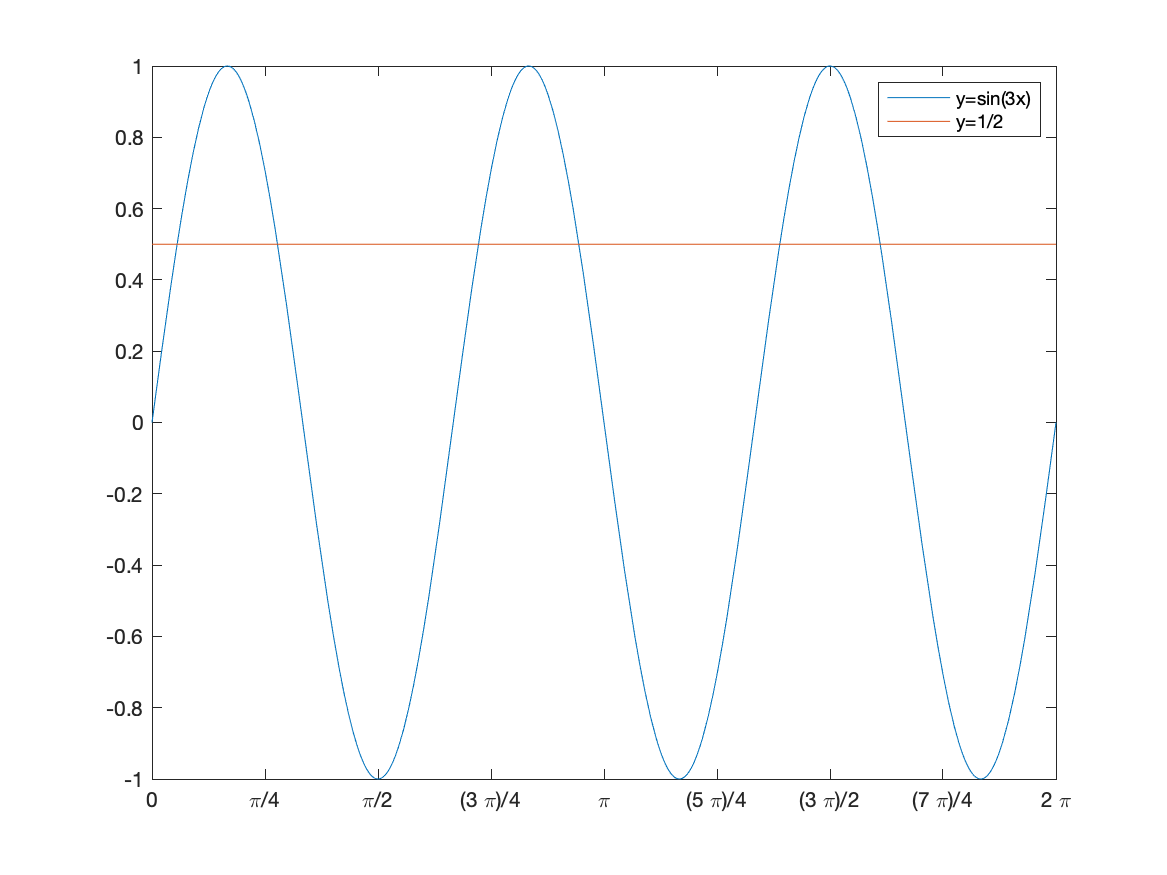

You should have seen how to solve trigonometric equations (an equation containing trigonometric functions) in Precalculus. In general these are quite difficult to solve, however Matlab can handle many kinds of Trigonometric equations. Try solving \(\sin 3x = \frac{1}{2}.\) with

eqn = sin(3*x)==1/2

solve(eqn,x)

Matlab returns \(\left( \begin{array}{c} \frac{\pi}{18} \\[5pt] \frac{5\pi}{18} \end{array}\right)\) which are indeed solutions to the equation. However, these two values are not the only solutions. Recall that the solution(s) of an equation is/are the point(s) of intersection of the graphs of the functions on either side of the equation. If we type:

fplot([sin(3*x),1/2],[0,2*pi])

S = sym(0:pi/4:2*pi);

xticks(double(S))

xticklabels(arrayfun(@texlabel,S,'UniformOutput',false))

where the last three lines gives nicer tick marks (See Chapter 2). The result is a plot the functions $f(x)=\sin 3x$ and $g(x)=1/2$ on the interval $0\leq x\leq 2\pi$:

On the interval that we plotted, there are 6 intersection points, but if we changed the plotting interval, that would change. There are actually an infinite number of intersection points.

Notice that the solutions found are the smallest intersection points in the plot above. The next couple of sections will show how to find all solutions and then solutions on a given interval.

Finding all solutions to a trigonometric equation

We now find out how Matlab can find all of the solutions above. If we enter:

[solx,parameters,conditions] = solve(eqn,x,'ReturnConditions',true)

Matlab returns 3 things:

\(\text{solx} = \left( \begin{array}{c} \frac{\pi}{18} + \frac{2\pi k}{3} \\[5pt] \frac{5\pi}{18} + \frac{2\pi k}{3} \end{array}\right)\) \(\text{parameters} = k\) \(\text{conditions} = \left(\begin{array}{c} k \in \mathbb{Z} \\ k \in \mathbb{Z} \end{array} \right)\)

The three are named what they are because we called them those in the solve command above.

-

The

solxis the all solutions. There are in pairs and you can think of them as paired from the plot above along each hump of the sine curve. -

The

parametersvariable lists the parameters (note the $k$ in thesolx). -

The

conditionslists what values the parameters can take on. In this case, $k$ can take on any integer.

If we are looking for all solutions to the solution, then the information in solx is the result or

\(\frac{\pi}{18} + \frac{2\pi k}{3}, \frac{5\pi}{18} + \frac{2\pi k}{3}

\qquad \text{for $k \in \mathbb{Z}$}\)

Exercise: solutions to trigonometric equations

Find all solutions to $\tan 2x = 1$.

Finding solutions to equations on an interval

In this section, we will find the solutions to $\sin 3x=1/2$ on the interval $0 \leq x \leq 2\pi$. The following command will do this

assume(conditions)

restriction = [solx > 0, solx < 2*pi];

solk = solve(restriction,parameters)

valx = subs(solx,parameters,solk)

There’s a lot to unpack here and we’ll walk through what’s going on:

assume(conditions)says that we will assume the symbolic variables in theconditionsvariable. That is that $k$ is an integer.- The line

restriction = ...puts the interval that we wish to solve and stores it in a variable. - The line

solk = ...solves for the parameters $k$ that give the restriction. The results are 0,1,2. - The line

valx = ...then finds the values of $x$ for these values of $k$. The result is

Exercise: Finding solutions on an interval

Find all the solutions for $2\cos 4x =\sqrt{2}$ on $[0,\pi]$.

Exact versus approximate solutions

Above, we solved,

\(x^{3}+3x^{2}-11x-10=0\)

and got an array of something called root, but wasn’t helpful. If we add:

eqn = x^3+3*x^2-11*x-10==0

solve(eqn, x, 'MaxDegree', 3)

which says to solve this up to a maximum degree of 3. The result is:

\[\left(\begin{array}{c} \frac{14}{3 \sigma_2} + \sigma_2 -1 \\[5pt] -\frac{7}{3\sigma_2}-\frac{\sigma_2}{2}-1 - \sigma_1 \\[5pt] -\frac{7}{3\sigma_2}-\frac{\sigma_2}{2}-1 + \sigma_1 \\ \end{array} \right)\]where \(\sigma_1 = \frac{\sqrt{3}\left(\frac{14}{3\sigma_2}-\sigma_2\right)i}{2}\) \(\sigma_2 = \left(-\frac{3}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{108}\sqrt{10733}i}{108}\right)\)

in short, this seems like a crazy answer. This is exact however and comes from a cubic formula that is much more complicated than the quadratic formula. The $i$ is the imaginary unit $\sqrt{-1}$, however, we will see these solutions are all real. Matlab just isn’t good at making clean answers.

In this case, I think numerical approximations are more insightful. The command vpasolve will do this for us:

vpasolve(eqn)

returns \(\left(\begin{array}{c} -4.8445196774478780056996095605694\\ -0.78500444582226096325038188120832\\ 2.6295241232701389689499914417777 \end{array}\right)\)

The vpa stands for variable-precision arithmetic, which basially means that this can be solved for any precision.

Solving Inequalities

Another important mathematical technique that a CAS is generally good at is solving inequalities, like $4x+3>5x-7$. However, if we enter

solve(4*x+3>5*x-7)

Matlab returns 9. Huh? (Seriously, I can’t figure out what this is doing). We need to add some options to the solve command.

[xsol,params,cond] = solve(4*x+3>5*x-7,x,'ReturnConditions',true)

returns $x$, $x$ and then for the third (the cond variable)

\(x<10\)

which is what we’re looking for. If we change the > to >= for $\geq$, then note that the solutions will switch to $x\leq 10$.

If we enter

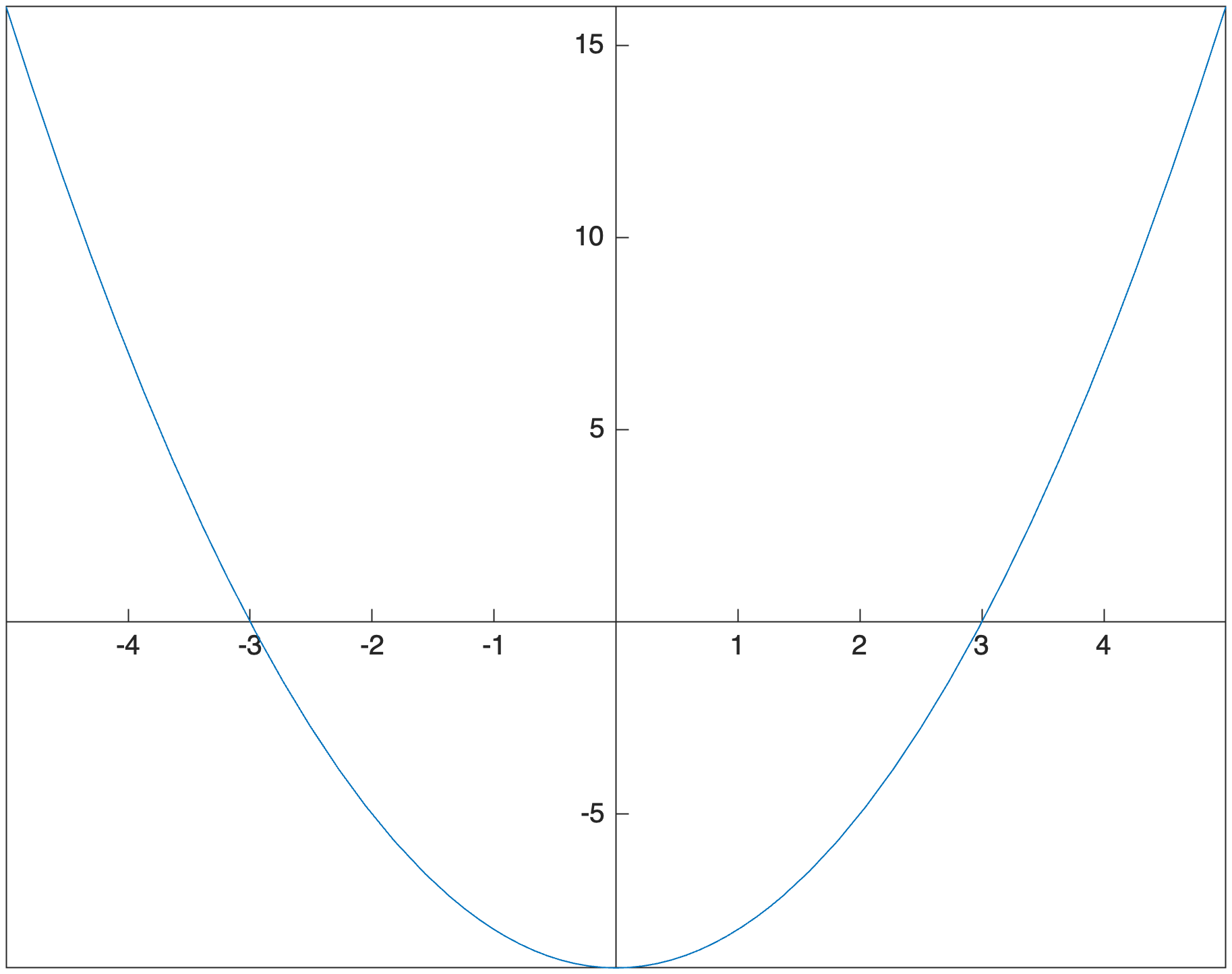

[xsol,params,cond] = solve(x^2-9>=0,x,'ReturnConditions',true)

the important part returns the array \(\left(\begin{array}{c} x \leq -3 \\ 3 \leq x \end{array}\right)\)

which is the union of the two intervals or \((-\infty,-3) \cup (3, \infty)\)

This should make sense if we plot the function $x^2-9$, then the result is

And you should notice that on the invervals $(-\infty,-3]$ and $[3,\infty)$, the function is above the $x$-axis.

If we switch the inequality sign and enter

[xsol,params,cond] = solve(x^2-9<=0,x,'ReturnConditions',true)

The result for cond is

\(\left(\begin{array}{c}

-3<x\wedge x<3\\

y\in \mathbb{R}

\end{array}\right)\)

and this can translate to the interval $[-3,3]$.

Getting Answers that make more sense

Consider the inequality $e^{2x} > 3$. If we solve this in Matlab with

[solx, param, cond] = solve(exp(2*x)>3,'ReturnConditions',true)

matlab returns: solx $= i\pi k +y$, param $=(k\;\;y)$, cond$=\log(3) < y \wedge \; k \in \mathbb{Z}$

This is quite confusing. What is going on here is that Matlab is solving this in general by assuming that $x$ could be a complex number. To handle this, you’d have to consider complex analysis, which is far beyond this course.

We can tell Matlab though to help us and use only real values. If we instead do:

[solx, param, cond] = solve(exp(2*x)>3,'ReturnConditions',true,'Real',true)

Then matlab returns solx $=x$, param=$x$ and cond=$\frac{\log(3)}{2} < x$ and this is the answer we seek.

Finding the domain of a function

Matlab can be helpful for finding the domain of functions, however, we need to recall some basics of functions. Recall that the domain of $\sqrt{x}$ is $[0,\infty)$, or the inside must be greater than or equal to zero. We can then use Matlab to help find say the domain of $\sqrt{5x-x^{2}-4}$, by solving

[xsol,params,cond] = solve(5*x-x^2-4>=0,x,'ReturnConditions',true)

and the interesting part of the solution is the cond variable, which returns

\(\left(\begin{array}{c} 1\leq x\wedge x\leq 4\\ y\in \mathbb{R} \end{array}\right)\)

which is Matlab’s nonstandard way of saying that this is the interval $[1,4]$, so this is the domain of $\sqrt{5x-x^{2}-4}$.

Exercise: Finding the domain

Find the domain of each of the following

- $\dfrac{1}{x^{2}-16}$

- $\ln(5x+7)$

- $\sin^{-1}(3x^{3}+5)$

Hint:

- it’s easier to solve the bottom equal to 0, then exclude it.

- recall that the natural log in Matlab is

logand you’ll need to recall the domain of it, then restrict the inside, just like the square root above. - what is the domain of the inverse sine?

Inverse Functions

Recall that the inverse of a function $f(x)$ is a function $g(x)$ if $f(g(x))=x$ and $g(f(x))=x$. For example if \(f(x) = \frac{3x+2}{x-1} \qquad g(x)=\frac{x+2}{x-3}\) then

f(g(x))

returns:

\[\frac{\frac{3\,\left(x+2\right)}{x-3}+2}{\frac{x+2}{x-3}-1}\]but that doesn’t look like $x$, so simplify it and you will get $x$. Simiarly

simplify(f(g(x)))

returns $x$.

Finding inverse functions

Matlab is also very helpful in finding inverse function. Let’s say we have the function \(f(x) = \frac{7x+4}{3x-2}\)

we can find the inverse by solving

syms y

solve(f(y)==x,y)

and Matlab returns \(\frac {2x+4}{3x-7}\)

If you set g(x) equal to this, then you can show the inverse relationship like we did above.

The inverse and domain and range

This shows how we can use the domain of a function and get an inverse of the restricted part of it. This is a more complex function than is typically seen in a Precalculus class, but Matlab allows us to do harder problems because much of the difficult algebra is done for us.

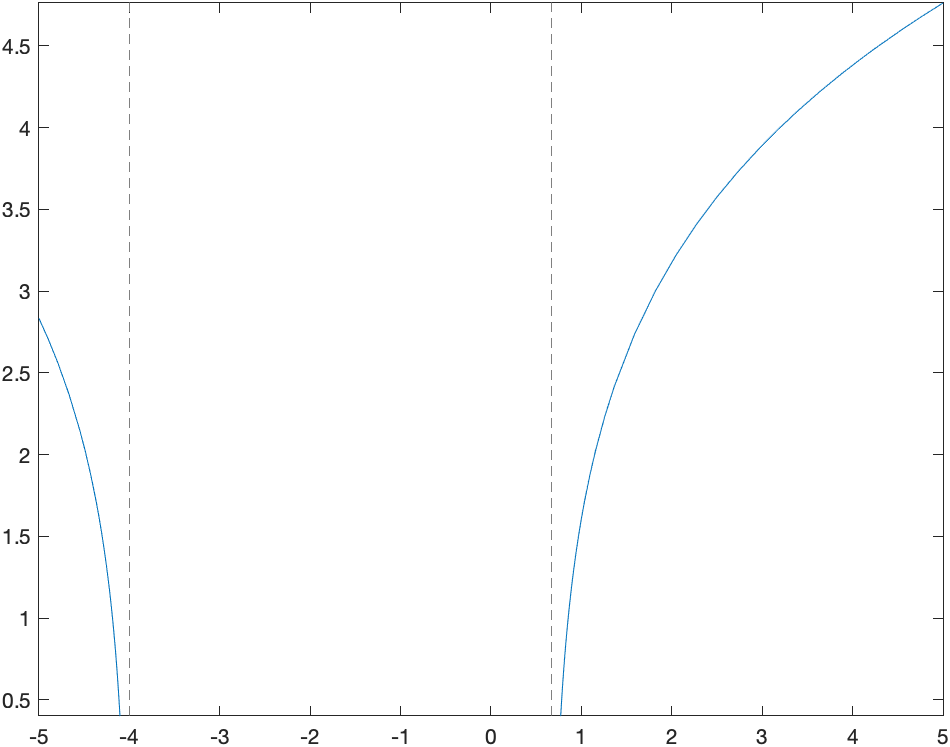

Let’s consider the function

\(f(x) = \ln\left(3\,x^2 +10\,x-8\right)\)

remembering that Matlab using log for natural log.

-

Plot the function.

You should see the following:

-

Find the domain of $f$.

We find the domain by solving the inside greater than zero:

[xsol,params,cond] = solve(3*x^2+10*x-8>0,x,'ReturnConditions',true)and this results in the interval $(-\infty,4)\cup(2/3,\infty)$. You can see in the plot that the only parts of the graph of the function are on these intervals, and it isn’t clear from the plot, but now it there are two vertical asymptotes of $x=-4$ and $x=2/3$.

-

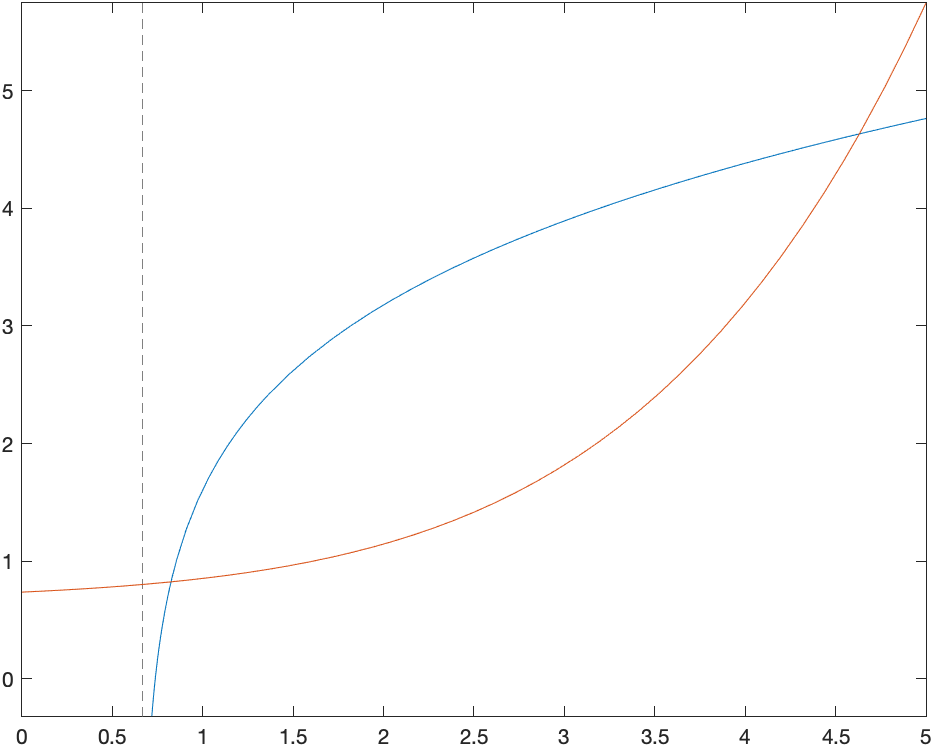

Restrict the function $f$ to $x>2/3$ and find the inverse of this.

We find the inverse of it by

invf = solve(f(y)==x,y). There is a warning and two solutions, this is because inside the log, there is a quadratic. Looking carefully at the results, the first solution is always negative and the second solution is always positive. The one we are looking for is the 2nd one.g(x) = invf(2)The (2) means to take the second element of the array. (Note: we will explain this in the next chapter)

-

Graph the function and its inverse. What relationship do you notice.

If we graph the two, for example

plot([f(x),g(x)], [0 5])then you get:

and you should note that they look like inverses because they are symmetric across the line $y=x$.

Odd and Even functions

Recall that an odd function satisfies $f(-x)=-f(x)$ for all $x$ on its domain and an even function satisfies $f(-x)=f(x)$ for all $x$ on its domain. Here’s a nice way to show these are satisfied in Matlab.

Show $f(x)=x^{3}$ is an odd function. It seems logical to show in Matlab f(-x)=-f(x). In this simple case, both sides are the same, so it seems it is an odd function. Let’s look at a more complex function,

\(f(x)=\frac{4x^{3}+2x}{x^{2}+5}\)

and in Matlab, we do f(-x)=-f(x), then Matlab returns

\(-\frac{4\,x^3 +2\,x}{x^2 +5}=-\frac{4\,x^3 +2\,x}{x^2 +5}\)

which shows that the function is odd. However, this doesn’t always work, however, we can rewrite $f(-x)=-f(x)$ by adding $f(x)$ to both sides to get $f(-x)+f(x)=0$. If we type f(-x)+f(x) into Matlab, we get 0, however if you don’t get a zero, try doing simplify(f(-x)+f(x)).

Exercise: Even and Odd Functions

- Show that $g(x)={\rm e}^{x^{2}}$ is an even function.

- Is $h(x)=\sqrt{3x+4}$ even, odd or neither.

Numerators and Denominators

Recall that a rational function is a a polynomial over another polynomial. Examples include \(\frac{1}{x}, \frac{x^{3}-3x}{x^{2}+1}, \frac{15x^{5}+3x^{2}}{4x^{2}+2}\)

And recall that we need to examine the individual numerator and denomiator to find $x$-intercepts and vertical asymptotes. To get these, we can use the numden command. For example, if

\(g(x) = \frac{4x^{3}-16x}{x^{2}-9}.\)

then both the numerator and denominator are returned with

[num,den] = numden(g(x))

which returns the top and bottom of the fraction. Now that we have these, let’s

- Find the domain of $g$

- find the $x$-intercepts of $g$

- Find the vertical asymptotes.

Since, we can’t divide by 0, we need to know where the denominator is 0 or

solve(den==0)

resultng in $-3$, and $3$. Therefore, the domain is $(-\infty,-3)\bigcup(-3,3)\bigcup(3,\infty)$.

For the answer to 2, we need to find the zeros (roots) of the top and

solve(num==0)

will return 0,-2,2. And the answer to the 3, is the zeros of the denominator or

solve(den==0)

which returns -3,3. Recall that this means the asymptotes, which are lines, are $x=3$ and $x=-3$.

Partial Fractions

The technique of partial fractions come up in many areas in mathematics including the integration of rational functions and finding inverse Laplace Transforms (in differential equations). An example is if we have the following rational function: \(R(x)=\frac{2x-2}{x^{2}+4x+3}\) and if we wish to write it as the sum of two simpler forms: \(\frac{4}{x+3}-\frac{2}{x+1}\)

The technique of going from a general rational function to a sum of simpler rational functions is called partial fractions. To do this, we recognize that if we factor the denomiator of $R$ or $(x+3)(x+1)$ so we hope to write: \(\frac{2x-2}{x^{2}+4x+3} =\frac{A}{x+3}+\frac{B}{x+1}\) or finding $A$ and $B$. Multiplying through by the denominator of $R$ results in \(2x-2 = A(x+1)+B(x+3)\) or \(2x-2=Ax+Bx+A+3B\)

at this point we equate coefficients by finding the coefficients of the $x$ term and the constant term on either side of the equation. This results in two equations: \(\begin{array}{rl}2&=A+B\newline -2&=A+3B\end{array}\)

subtracting these, results in $4=-2B$ or $B=-2$ and then you can find $A=4$. This shows that

\[\frac{2x-2}{x^{2}+4x+3}=\frac{4}{x+3}-\frac{2}{x+1}\]Using a CAS to find partial fractions

We start again with

R(x) = (2*x-2)/(x^2+4*x+3)

and get the numerator and denominator:

[num,den] = numden(R(x))

and we factor the denominator:

factor(den)

returns $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} x+3 & 1+x \end{array}\right)$ which is Matlab’s way of writing: $(x+3)(x+1)$,

Therefore we can write the original function as: \(\frac{2x-2}{x^{2}+4x+3}=\frac{A}{x+3}+\frac{B}{x+1}\) by typing:

syms A B

eqn = R(x) == A/(x+3) + B/(x+1)

remembering to define $A$ and $B$ as symbolic variables. Then we multiply through by the denominator of $R$. Then

simplify((eqn*den)

returns \(2\,x=A+3\,B+A\,x+B\,x+2\) and oddly, it moved the 2 to the right hand side. We now need to equate the coefficients.

First, let’s get the coefficients on both sides:

leqn = coeffs(lhs(eqn2),x,'All')

reqn = coeffs(rhs(eqn2),x,'All')

where the 'All' is needed to ensure that both the coefficient of x as well as the constant is included. Also, the order of the cofficients in the resulting array is important.

We set up the equations:

leqn(1)==reqn(1)

leqn(2)==reqn(2)

which returns the equations: \(\begin{array}{rl} 2 & = A + B \\ 0 & = A+ 3B+2 \end{array}\)

and then we solve these with the following:

[a,b]=solve([leqn(1)==reqn(1),leqn(2)==reqn(2)],[A,B])

and the answer is $A=4, b=-2$, so then

subs(eqn,[A,B],[a,b])

results in \(\frac{2x-2}{x^{2}+4x+3}=\frac{4}{x+3}-\frac{2}{x+1}\)

Converting an expanded form back

How do you reverse the partial fraction? If you are doing it by hand, it is simply finding a common denominator and combining terms. In Matlab,

simplifyFraction(rhs(eq5))

returns \(\frac{2(x-1)}{x^{2}+4x+3}.\)

which is what we started with.

Exercise: Partial Fraction

Find the partial fraction form of \(\frac{9x^{2}+8x-4}{x^{3}-4x}\) using the steps above. Check your answer by reversing the partial fraction form.

Using the built-in method

Of course, Matlab can do all of these steps at once. If we use the $R$ from above, typing

partfrac(R(x))

returns \(\frac{4}{x+3}-\frac{2}{x+1}.\) which of course is much easier, but note that the steps above remind us how this is actually done.

Exercise: Partial Fraction, built-in

Find the partial fraction form of \({\frac {4\,x^{6}+15\,x^{5}+34\,x^{4}+66\,x^{3}+94\,x^{2}+56\,x+40}{x^{4}+2\,x^{3}+5\,x^{2}+8\,x+4}}\) using the built-in method.

Long Division of Polynomials

Another common technique needed to do is long division of polynomials.

For example, from Purple Math’s long division page, if we want to do $(x^{2}-9x-10)\div (x+1)$, the result is $x-10$.

Matlab will do this using simplify. That is, if

\(R(x)=\frac{x^{2}-9x-10}{x+1}\)

and then performing

simplify(R)

returns $x-10$. However, (from another PM page ) consider if

\(Q(x)=\frac{3x^{3}-5x^{2}+10x-3}{3x+1}\)

then simplify(Q) returns $Q$ again. But we may want to actually do the long division.

The command polynomialReduce returns the quotient and remainder using polynomial long division.

[r,q] = polynomialReduce(3*x^3-5*x^2+10*x-3,3*x+1)

returns $-7$ and $x^{2}-2x+4$ for the remainder and quotient. This means that we can write: \(Q=\frac{3x^{3}-5x^{2}+10x-3}{3x+1}= x^{2}-2x+4+ \frac{-7}{3x+1}\)

and to determine that this worked, typing

simplifyFraction(x^2-2*x+4-7/(3*x+1))

returns the improper form of $Q$ as above.

| Previous Chapter | Return to all notes | Next chapter |

-

Solving equations are difficult for many reasons. One is that they require you to categorize the equation to determine the type (linear, quadratic, exponential, etc) and they to know (or be creative) to go through steps that result in the solution (or solutions). Another reason solving is difficult is that many equations do no have an solution that results from performing algebraic steps. ↩